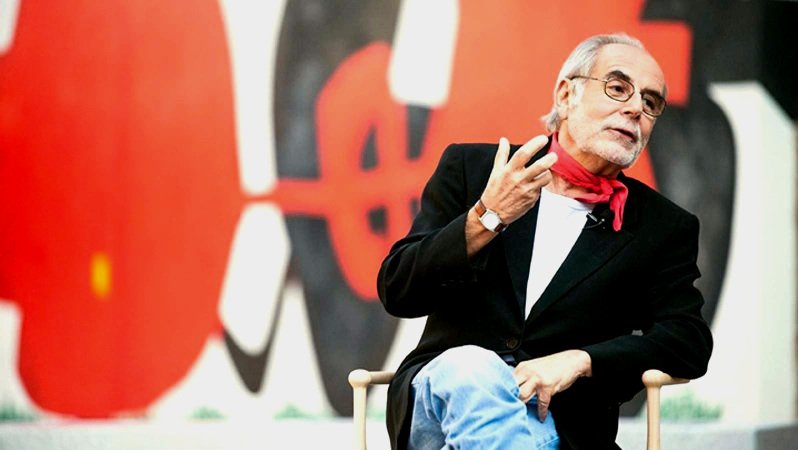

Arranz-Bravo liked to say, “friendship is like a rock in the landscape,” something that is always there, immovable in nature, regardless of the adverse winds of life. Arranz-Bravo was a rock in the landscape of art.

In 1966, Arranz-Bravo raised the great symbol of new artistic progress in Spain: the Tipel factory murals which were a commission on which he worked with his dear friend, Rafael Bartolozzi. Arranz-Bravo was there during the sixties and seventies, alongside Picasso and Miró at the Sala Gaspar Gallery in Barcelona. He was also a rock during the eighties, through his extended artistic endeavors, from Tarragona to Cadaqués in Spain. Internationally, his presence and influence continued onward in the galleries and art centers through the decades.

More recently, Arranz-Bravo was a pillar through his foundation in l'Hospitalet, helping young artists, with whom he has always surrounded himself. He knew that art is a deep and long career in which the artist leads, as suggested by the poet Kavafis, a “flaming candle”: a flame which must be raised and nurtured when you have strength, and passed on, when life declines.

Arranz-Bravo has been the “bearer of the flame” of the vital and open avant-garde of Joan Miró, his mentor. He also embodies the rigorous inward gaze, of Rembrandt or Dieter Roth, bringing together two extremes of the psychological, intense and expressive nature of art in which he always mirrored himself.

Arranz-Bravo also often told us: “to be human is to occupy in a good way a space,” which for him was summed up in two actions: working like a madman, and methodical consistency. He knew that genius is not the one who expresses himself by divine will, but the one who knows how to give continuity to the artistic work to fulfill his deepest pictorial intuitions. Arranz-Bravo served this goal throughout his entire life, 364 days a year, the only break being taken on May 1, International Workers' Day.

Arranz-Bravo was pure vitality, with overflowing and irrepressible energy; so much, that he still had some to share with those privileged enough to be around him. I first met him when I was a student, and interviewed him one afternoon to write an article for Bonart magazine. After a week, he called me to commission a 300-page book that would become a document of his foundation’s collection. A few years later, I would be invited to assist him with the establishment of his foundation. Going to Vallvidrera to visit with him was a balm for me: to see the working capacity of that man of retirement age, who awoke at five every morning and painted with a vitality that also emanated from his work. It was a dose of energy that became a drug for me.

Arranz-Bravo gave us method, work, efficiency and passion for art and culture. He pushed us into action. He could not stand the society of bureaucracy and a “let’s see” mentality. His life was conjugated only in the present tense, in which he lived with a demonic intensity. The directors of the Italian school in Barcelona, where he did his final mural project last spring, still remember when they asked him about the possibility of painting in the school. The next day they were shocked as Arranz-Bravo already had the project outlined and with a detailed work program.

Arranz-Bravo was very instinctive, but reason prevailed as a regimen: “the important thing in art is reflection.” “We humans don't reflect enough,” he used to say. His balance of instinct and reason allowed him to share his knowledge in a symbolic, universal way.

So, the importance of Arranz-Bravo’s work can be explained by the mixture of cultural dimensions that rarely occur in an artist: instinct, culture, intelligence, method, reflection and, finally, social connection. Arranz-Bravo was an asocial being. He always concentrated, monastically, on his “parallel reality” of painting. His work embodied the raw existence of the human condition, trapped in the reality of passions (tragic or vital). On the other hand, however, he liked to connect with life and humanity through art. Arranz-Bravo shared his work with the world: in factories, in the streets, in art centers (the famous mural in Eina school or the Institut de Fotografia de Barcelona), towns (the action “blue Cadaqués” during the eighties), the Ramblas (the symbol of l'Hospitalet, L'Acollidora), the squares (the Llibertat Bridge, also in l'Hospitalet), the schools (two painted schools in l'Hospitalet and one at the Italian school) or libraries (like the Tecla Sala). Arranz-Bravo was a total artist: both vertical (due to the depth or altitude of his art) and horizontal (due to the popular all-encompassing nature of his work).

There are still important pages to write about this outstanding man and his brilliant work. The energy that flowed from his hands ran parallel to the resoluteness of his character, always sincere and independent. Our endeavor in the coming years is to ensure Arranz-Bravo’s rightful place in history, and share the artist’s voice with future generations.

-Albert Mercade, Director of the Arranz-Bravo Foundation

March, 2024